When the Ricardo Legorreta Vilchis designed Camino Real Polanco The hotel was opened in Mexico city in 1968, three months before the city organized the Summer Olympics. It was immediately celebrated as an architectural masterpiece.

The most powerful unique feature, which was most defined, is undoubtedly the “fountain of eternal movement”, which was produced by the famous landscape architect Isamu Noguchi, which does not provide the calm or stately fountain that is common in other properties, instead a world of violent movement. The hotelHowever, the general aesthetics are strongly committed to the creative sense of modernist design by Legorreta and especially its passion for lively colors.

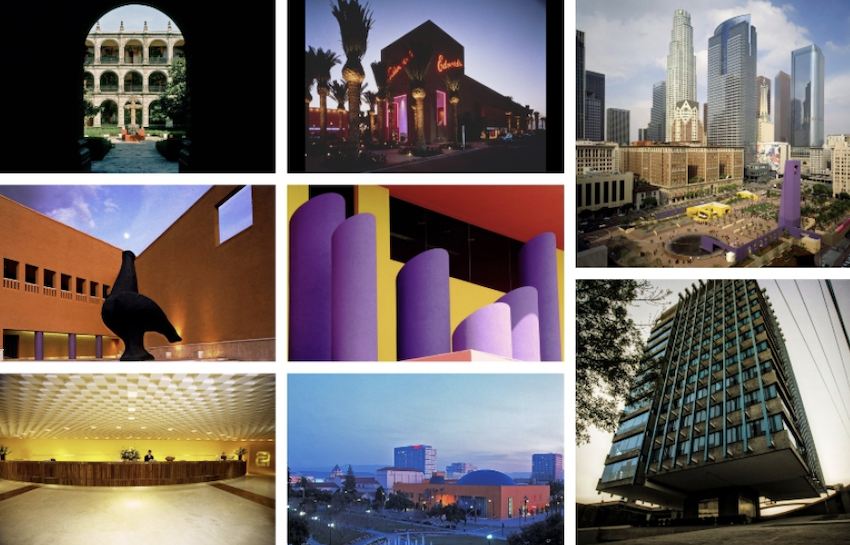

His often photographed entrance gate is, for example, a lively magenta-red-pink grid, which is derived from a strong yellow adjacent wall. This type of unmistakable color signature becomes a staple food of the Over 100 projects – Including numerous hotels and museums as well as private houses and public work – Legoretta, which were designed before his death in 2011, and strengthened his reputation as one of the greatest of all Mexican architects.

Legorreta's color concept

Legorreta's understanding of Color's ability to cause emotional reactions, he undoubtedly learned from his teachers at the University of Nacional Autónoma de Mexico (UNAM) in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It was certainly funded by mentors such as José Villagrán García.Father of modern Mexican architectureAnd the man who hired him before he graduated and was also influenced by the legendary architect Luis Barragán When the two became friends in the 1960s.

According to Legorreta, the man who was most clear his thinking on this topic was Chucho Reyes (Born Jesús Reyes Ferreira), the autodidactic painter who, like Barragán, came from Guadalajara. To Legoreta, Reyes was “The master of color who taught us everything.” In fact, you just have to look at Reyes 'work to see the light, brilliant purple, blues and yellow, which would later be tested in legoreta's designs, from the 10-story purple campanile in Los Angleles' Pershing Square (1993), which is seamless in the tech museum in innovation, in San, in San José (1998) in the eye, in San José, in innovation in the innovations in innovation, in innovation in innovation, in the innovation in innovation, in the innovation in HIS. Casa Greenberg (1991) and in his first landmark Camino Real.

This mix of these lively colors in a rich symphony – the artistic term is polychromy – was always intended in Legorreta's work and should meet a specific purpose. As he Once notedColor “Dramatized, evoked, creates emotional reactions, reinforces personal experience, offers energy for rooms and increases its presence.” He was so sensitive to these emotional currents that he chose colors that can change in order to reflect on changing moods when the natural light shifted into intensity throughout the hours of every day.

Such sensitivity would be remarkable in every artist, but it was particularly striking in one in a family of bankers.

The development of Legorreta's aesthetics

Legorreta was born in 1931 as the sprout of Mexico in Mexico in 1931 and could easily have entered the footsteps of his father Luis and Uncle Agustín, which had founded the country's largest bank (Bancomex). But when he was a teenager, he knew that he wanted to be an architect. After studying the Unam and spent a little more than a decade as an apprentice and later partner of Villagrán, he opened his own company Legorreta Arquitectos in 1963.

His first characteristic design for an automobile factory in Toluca was a liberating experience and an assertion of his very Mexican sensitivity. “When I built Automex, it was like an explosion in me,” he recalled in 1995 according to the Los Angeles Times. “A rebellion against all the discipline I knew and the foreign rule of my country. It was like” Viva Mexico! “And 'Viva the Mexican worker!' '' '

With the success of the Hotel Camino Real in 1968, he was not only recognized as a promising student of Villagrán and Barragán, but as a mature, independent artist. The Opening of the hotel was visited by President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and his uncle Agustín Legorreta López Guerrero. Both were reported to investors, his uncle in his role as President of Banamex at the time. Further commissions were rolled up, including for others Royal road Hotels in Cancún and Ixtapa.

Legorreta's work in the USA

Although most of his designs were still in Mexico and received at least one dozen in his home in Mexico city in the 1980s alone, commissions from international sources were increasingly received. These brought up his global profile, but also brought controversy, as a critic in other countries, such as the USA, not always so well with its clearly Mexican design philosophy. In the mid-1980s, the purple walls for the shopping center of $ 90 million in California in California were obliged by the city's mayor as “too bright, too depressing” and Legorreta in order to replace them with a more acceptable ocherhue.

“The incident taught me something about the profound differences that are among the surface similarities in Southern California with my homeland,” said Legorreta at the time. “Although the climate and topography are similar and a large part of the cultural heritage, California society is also more confident and less brave than ours, and this difference is reflected in architecture.”

In fact, only a few architects have ever accepted boldness like Legorreta, especially when it came to color. And so that you can see that the incident with Tustin had his principles rethinked, his Pershing Square project in Los Angeles turned around one a few years later 125 foot large purple bell tower. That was also controversial, but he never thought about changing it.

Definitely dead and legacy

In the last 20 years of his life, Ricardo Legorreta has worked with his son Victor. Since his death from liver cancer at the age of 80 in 2011, Victor has continued his father's legacy Legorreta + Legorreta. It is difficult to imagine that someone who corresponds to Ricardos flair for colors, but is based on the breathtaking Papalote Children's Museum – only four kilometers from the Camino Real in Mexico City – an eye for color can be a talent that runs in the family, just like banking.

Chris Sands is the local expert of Cabo San Lucas for the USA Today Travel website 10 Best, author of the Fodor's Los Cabos Travel Guidebook and an employee on numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Paiethole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily. His specialty are travel and lifestyle features related to travel trains that concentrate on food, wine and golf.