This article is part of our Museum Special Section about how artists and institutions adapt to changing times.

In the gilded age, when the newly wealthy Americans tried to advertise their social status at home and abroad, some of them turned to one that has long been a practice of the established rich: art collection.

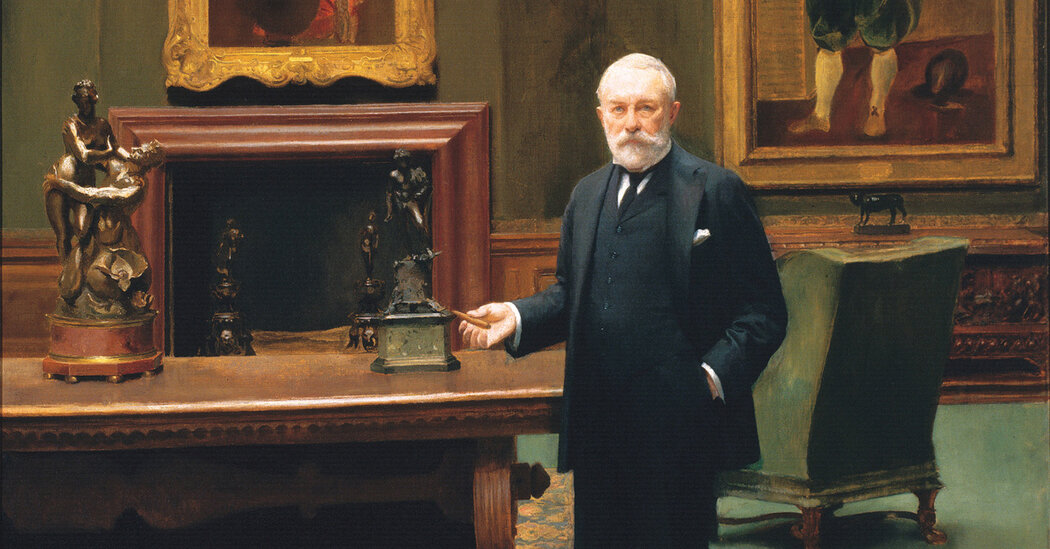

Henry Clay Frick, who made his luck in cola and steel, had appreciated art as a young man, especially as prints and sketches. “Some of them made themselves,” said Colin Bailey, director of the Morgan Library and Museum and expert for Frick.

But Frick's interest ultimately turned to higher works of the old masters of Europe such as Rembrandt and Vermeer as well as the creations of more modern geniuses such as Manet and Degas. For decades he acquired one of the best private collections in the world and exhibited them in a Fifth Avenue Mansion, which is now a large museum. The Frick Collection's house, newly renovated, was reopened in New York in April.

With the competitive zeal, which fueled his success in business, Frick competed for works of art against others who enjoyed enormous wealth: the banker JP Morgan; Peter Widener, founding organizer of United States States and the American Tobacco Company; and Isabella Stewart Gardner, founder of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

“He hated to lose a painting that he wanted,” said Ian Wardropper, who returned to the Museum that Frick had created after 14 years as director of the Frick Collection.

Frick's passion for the submission of the Fifth Avenue Mansion, with which he was built in 1913. In Wardropper's book “The Fricks Collect: an American family and the development of the taste in the gilded age,” he says some of Frick's interaction with another collective competitor, Benjamin Altman, the foundation of the B. Altman department in New York City.

The cloak operator writes that Frick was jealous of Altman's 90-foot art gallery in his new house in the Fifth Avenue and asked Roland Knoedler, the New York art dealer, to tell him the dimensions of the room. “When Frick's Gallery was completed in 1914,” wrote Wardropper in his book: “It was 96 feet long, the largest private gallery in New York.”

Before he died in 1919, Frick bequeathed his villa, in which he had lived together with his wife, two surviving children and his art to create a museum, and provided a foundation of $ 15 million to finance his maintenance and improvements. The museum was opened in 1935. Almost half of his 1,800 works were originally acquired by Frick.

Five years ago, the museum was closed for extensive renovation. The collection was temporarily moved to the former house of the Madison Avenue of the Whitney Museum of American Art, which is now located in the city center in Gansevoort Street.

During the renovation, the damn mansion lost its 149-digit, oval music room. But among other things, an auditorium with 220 seats under the garden of the 70th street (which are rebuilt); New entry points; A two -stage reception hall, a coat check and a café; and special exhibition galleries, among other things.

The original galleries of the first level received makeovers, while the living rooms on the second floor, which have been used as an office space for a long time and were excluded for visitors, were transformed into new galleries to show a collection of significant portraits, watches and other works.

The expansion and renovation, which cost 220 million US dollars, was led by Annabelle Selldorf of Selldorf Architects, with Beyer Blinder Belle Belle Architects and Planner and the garden designer Lynden B. Miller.

Master Craftspeople took care of many details, for example the creation of a new, self -supporting marble staircase to the second floor (Wilkstone from Paterson, NJ); Restoration of woodwork (crafty from West New York, NJ); Create the wall coverings of the green silk velvet in the West Galerie (Prellen of Lyon, France); Cleaning and updating the lighting (Aurora lamps, Brooklyn); And produce new tassels, fringes, cords and other frills throughout the house (Passement series Terred Paris).

When setting up his collection, Frick was often persistent in maintaining the works of art he wanted, experts said. He negotiated a Rembrandt self -portrait from 1658 for months before he bought a star of his collection. Then the painting by Knoedler, the head of Knoedler & Company, and another dealer who offered it for $ 225,000 was bought.

Frick finally lowered a deal for the payment of the 225,000 US dollars, but made up the last 25,000 US dollars by returning a painting by Jules Breton, which he bought 11 years earlier, according to Cynthia Salzman, author of “Old Masters, New World: America's Raid's Raid on the big pictures of Europe”.

“Frick had bought the painting for $ 14,000 and calculated that it was now worth 25,000 US dollars,” said Saltzman in an interview. “He paid the $ 200,000, returned the Breton and got the Rembrandt.”

Clothing director said that Frick had traditional flavors who preferred landscapes and portraits of famous men and beautiful women, over everything nervous. He usually passed on acts or religious paintings, with the exception of Giovanni Bellini's “St. Francis in the desert”.

Frick was born in West Overton, Pennsylvania, 40 miles southeast of Pittsburgh in 1849. His father was a farmer. The family of his mother had the old overtaking -Whiskey distillery.

Frick visited “a college office and worked as an accountant in the distillery and as an employee in a hardware store in Pittsburgh,” said Wardropper. Then he joined a cousin as a company's partner who produced cola, a fuel generated by heating coal.

“Starting with family loans, he finally bought his partners out and had a monopoly on the global supply of cola within a decade and was a millionaire,” said Wardropper. He later became a partner with Andrew Carnegie, the American industrialist.

Although Frick devoted himself to the public for the public and friends, it was known that he was ruthless in the business. In 1892 he made no forbearance when the composition of iron and steel workers voted for the work of the Carnegie Company in Hempstead, PA.

Frick hired Pinkerton detectives to convince the strikers to withdraw. Eight people were killed and many wounded in a gun battle. Frick was convicted.

Later this month, Alexander Berkman, a Russian anarchist, tried to murder when he damned in his office. Frick was shot twice – in the shoulder and neck – and stabbed it. But he dictated his mother and Carnegie a memo with the inscription: “Was shot twice, but not dangerous. There is no need to come home. I am still in shape to endure the fight.”

Frick continued from printing to buy works by French painters from the Barbizon School like Corot and Daubigny, said wardrobe. Then, possibly influenced by the taste of other wealthy collectors, he followed old masters.

From 1900 to 1909 Frick returned many Barbizon works and bought paintings from Vermeer, Salomon van Ruysdael and Hobbema as well as Rembrandt and English painters such as Gainsborough and Reynolds. In 1914 he bought paintings from Manet, Renoir and Degas.

Clothing director said that one of Frick's daughters, Helen Clay Frick, who died in 1984 and headed the collection after his death, was responsible for acquiring many of the early Italian Renaissance paintings, including works by Duccio, Cimabue and Piero Della Francesca. She also bought Ingres' painting “Comtesse d'Asonville” (1845), one of the most admired works by Frick.

Henry Frick acquired from the dealer Joseph Duveen, who also sold him a number of fragonard paintings entitled “The Progress of Love”, who are now in the renovated Frick area in Frick. The price was 1.25 million US dollars, the most expensive purchase of Frick.

In his later years, Kardreader said that Frick spoiled with a cigar in the evening in his hand to admire his collection. He remembered that Helen Frick said that a week before her father's death, she discovered that he was on a couch in one of the galleries, the two works he loved: Velazquez '”King Philip IV of Spain” and Goyas “The Forge”.

Frick said it makes sense to keep part of her assets in art that surrounds it and not only invests in bonds. With the former he said: “You can draw your dividend every day.”