4 Min. read

While public climate finance increased between 2017 and 2022, the amount going to food and agriculture decreased during this period.

There is a critical gap between the money the food system needs to protect itself from the climate crisis and the funding it actually receives, according to a new report.

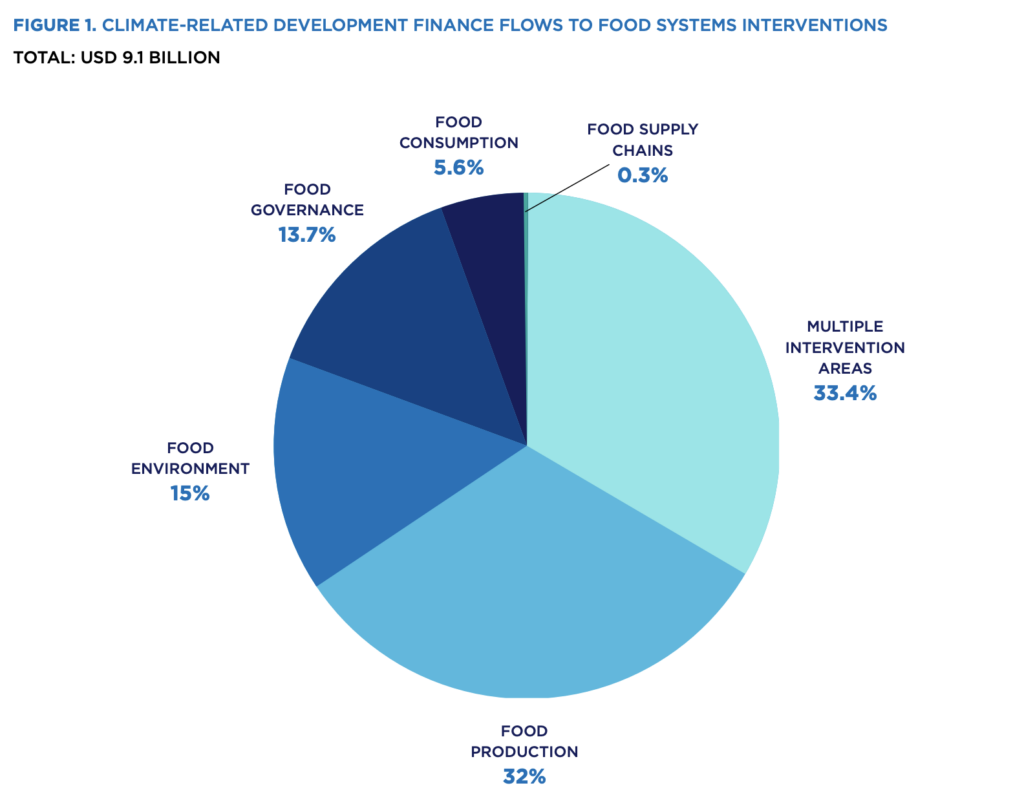

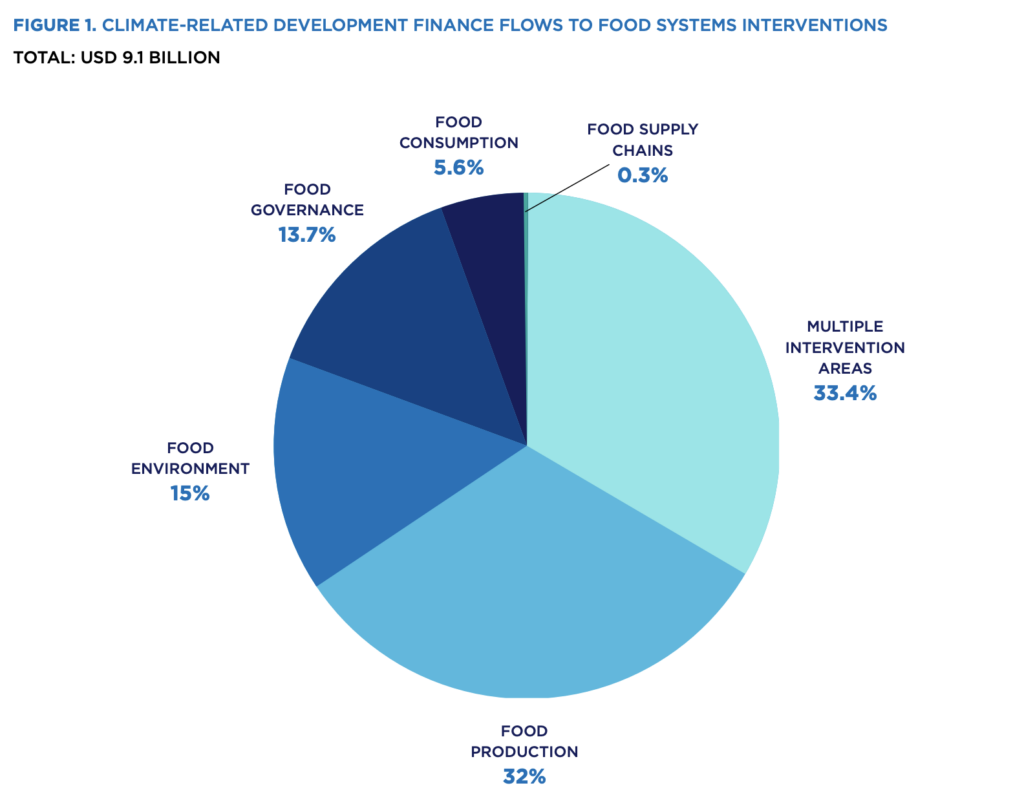

Although public funding for climate change adaptation and mitigation almost doubled to $640 billion between 2017 and 2022, the share of investments allocated to the agri-food sector fell from 3% to 2 .5% (total $16.3 billion). And that share fell to just 1.5% (or $9.1 billion) for sustainable food system interventions.

However, according to the Global Alliance for the Future of Food (GAFF), food and agriculture are responsible for a third of global greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating a climate crisis that disproportionately affects small farmers, fishermen, pastoralists and indigenous peoples.

The report, Public Climate Finance for Food Systems Transformation, calls for urgent “orders of magnitude” increased funding for, among other things, greener agricultural production, healthier diets and reducing food waste, which can bring both environmental and economic benefits.

“Transforming food systems is critical not only for climate stability and adaptation, but also for supporting the very people and communities most affected by the climate crisis. We know that farmers, fishermen and indigenous peoples around the world are critical to building resilience,” GAFF Deputy Director Lauren Baker and Executive Director Anna Lappé said in a joint statement.

“The need for sustainable, agroecological food systems to receive significantly more climate finance is more urgent than ever,” they added.

NDCs must redirect harmful subsidies

The majority (68%) of funding allocated to sustainable food activities came in the form of grants and loans from governments, while 27% came from multilateral organizations such as development banks. Mitigation projects accounted for a slightly larger share (41%) than those focused on adaptation (35%).

But consumption-related efforts – transitioning to healthy and sustainable diets and reducing food loss and waste – generated less than 6% of the $9.1 billion invested, despite being the two most effective measures to reduce agricultural emissions acts. A third of the funds went to several intervention areas, while another 32% was earmarked for food production.

All of this is a fraction of the $500 billion experts say is needed to transition to a sustainable food system, meaning annual climate finance for the sector would need to be increased nearly 55-fold.

Currently, 90% of countries' Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) identify mitigation and adaptation in the agricultural sector as a climate priority, but the level of public funding currently flowing into the food system is not consistent with a 1.5°C future.

In their updated NDCs next year, governments must outline plans to redirect $670 billion in annual polluting agricultural subsidies to environmentally friendly products, GAFF says.

And intensifying investments must occur across all areas of the system, helping to transform agricultural practices and production, enable dietary transition, combat food waste and support inclusive, equitable governance and decision-making.

The hidden cost of the current food system to human and planetary health is estimated at $12.7 trillion to $15 trillion per year. But major investments in transforming food systems can deliver at least $5 trillion in annual economic benefits from a shift to sustainable agriculture, reversing biodiversity loss, reduced irrigation water needs, reduced nitrogen use, etc Restoration of ecosystems and a lower result results in climate footprint.

The responsibility should not lie solely with the global south

New financial instruments must increase climate finance from the global north to the south, a region typically worst hit by the climate crisis.

“The costs of transforming food systems in the Global South cannot be borne by these countries alone, given the legacies of colonialism, extractive economies, debt burdens, corporate vested interests and unequal power dynamics.” [the] “Attracting resources and finance from poorer to richer regions of the world,” the report says.

According to GAFF, governments must ensure that investing in transforming the food system is a priority in mitigating and adapting to climate change, enabling measures to finance safety nets, enable reskilling, and fund adequate rural infrastructure and regulatory frameworks.

Lawmakers must also put in place coordination mechanisms to ensure that financial flows flow into all key policy areas through comprehensive projects, including climate, food security and biodiversity.

Climate funds, meanwhile, should aim to increase concessional, below-market financing through mixed financing instruments. “This may include leveraging private finance to scale and fund local and national food and nutrition security, agroecology and regenerative food systems projects in line with local and national food systems transformation priorities,” the report says.

Financing for small farmers and indigenous peoples who currently do not have direct access to climate finance from international sources should be significantly increased. And donors should take a food systems approach to climate finance to boost investment across all parts of the sector.