Note from the publisher: This essay by Luca Johnson was written in the Mercier Gallery in Paris in May on the occasion of his father Mitchell Johnson's exhibition in May. We think it's a great Father's Day contribution!

A few times a week, my phone will buzz in my desk with an SMS from my father with a new painting on my desk. I always start my work and take a moment to meditate about it.

I particularly noticed a work a few weeks ago – “Corn Hill (Albers).” (shown above) The secret of the fence and its ladder -like shadow, which moved into space, continued in the following days. He told me that he lasted almost a year for him to finish, and showed me the photo of Josef Albers of a fence from Mexico, who inspired the composition.

For me, however, the work remembered with the idea of a fence of one of my father's favorite painting – “The Face” by Camille Pissarro, which was housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington. DC This work from 1872 (see below) is a landscape of the French landscape with a fence that brings itself into the background of the canvas.

Those who are familiar with my father's work are probably aware of Josef Albers and Giorgio Morandi's influence. On the occasion of his exhibition at Galerie Mercier in Paris, it is also important to look at his work in the context of the French paintings of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Before Johnson started in Parsons in New York, he worked in applied research in Washington, DC for two years, spent his evenings at the Washington Studio School and as a lecturer in the National Gallery of Art. Before he studied under the leading American post -war artists Leland Bell, Paul Ressika, Jane Rivers and Robert de Niro, Sr. Parsons in New York – and before France's first visit, spent the French paintings from the renowned Mellon collection of the NGA in the French painting for the first time.

When I was a child, my father and I went to Annapolis, Maryland every year, to visit my grandfather. Every year we have three a pilgrimage to the National Gallery. My father led us professionally through the labyrinth of the galleries, whereby our visit always culminated in a separate gallery in the west building, in which the smaller paintings donated by Paul Mellon were housed in the Impressionist. We looked closely at Bonnard and Vuillard before we always paused in front of “the fence”. “This is my favorite,” my father always said.

“The fence” requires that you pause and look. Like “Corn Hill (Albers)”, Pissarro uses the structure of the wooden fence as a visual invitation to lure the viewer into the composition. While for Johnson, the fence in his difficult -to -grapping morning shade, Pissarros fence leads us on the way of the lonely figure on the right and encourages us to take a closer look through the branches and appreciate the country houses illuminated in the background. Pissarro works on the edges of the canvas – the path, branches and fence extend to the limits of the composition – fill the room so that every brush stroke and every detail is targeted.

Pissarro painted this work in 1872 after he had returned to Pontoise during the French Prussian War from exile in England. Prussian soldiers had occupied his studio during the war and used his canvas as floor mats against the muddy country premises and destroyed a large part of the work he had left behind. On a symbolic level, “the fence” feels like an ode to the innocence of country life, against which the Prussians injured – clearly in the delicate body language of the man, who leaned against the fence, weighed head in his palm of his hand, crossed his leg nonalant. Pissarro was a pronounced anarchist throughout his life and, through his work, showed a deepweight in front of the proletariat, making the everyday farm with the same respect that would be granted to an aristocrat.

Pissarro's representations on the French landscape mainly come from the Vallée de l'iise – a collection of small cities in the northwestern area of Paris, which are located on the Oise River on the Oise River. In November 2024 I drove to the city of around 45 minutes in front of the city with a rer. I walked the shores of the Oise to Pontoise and found a landscape that largely remained in the scenes of the late 19th century painted by Pissarro, daring wild trees, which move into the water, the same factory that sits on a fork in the river.

I undertook the trip to the Vallée de l'iise to experience the landscape and understand the space that shaped Pissarro's vision, but also appreciate the dichotomy between its provincial and Paris existence. Pissarro fought his personal finances all his life and moved his family several times. Sometimes he was based on the monetary generosity of his good friend Monet. On several occasions, when he came into a little money, he dared to go to Paris and rented apartments from the Opéra, the Jardin des Tuileries and the Pont Neuf. His Parisian existence always had a temporality – when his rental contract, his money or patience went out with the big city, he retired to the landscape, the place where he really felt at home. After an afternoon in the calm of the Vallée de l'iise, the shock to the senses is when it steps out of the train from Gare Saint-Lazare.

A similar dichotomy in Paris/Province also exists in my father's career. Like Pissarro, he first flew through her landscape with France as an artist before turning into Paris. My father came to France for the first time in 1989 and spent a few days in Paris before going to Marseille overnight. He rented an apartment in the small town of Meyreuil from the village doctor and spent several months in the shadow of Mont Sainte-Victoire to Malen-Des Legendary Berg with a flat, omnipresent mountain in the work of Paul Cézanne. Before Cézanne performed his legendary works near Aix-en-Provence, he spent years on the side of Pissarro on the banks of the Oise and, alongside one of the fathers of impressionism, dominated his meaning for space and form.

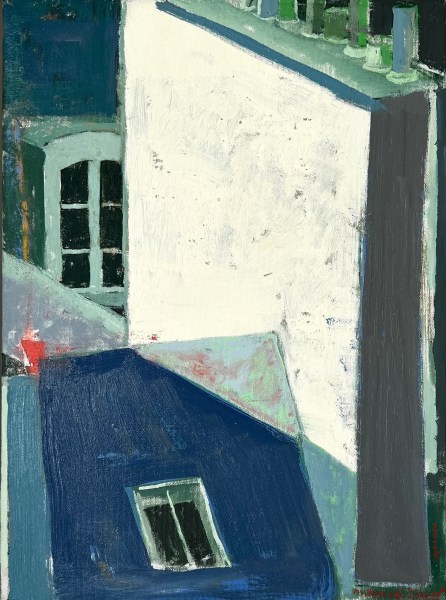

My father from France's work turned to the landscapes of Meyreuil for a long time. Despite numerous visits in Paris in the decades after his first trip to Europe – in apartments in the whole city from Ménilmontant to Marais to La Muette – he only interested him in autumn 2021 when he was really interested in making compositions from Paris for the first time. He stayed in the 8mm in Rue de Colisée and spent hours at the window of a small apartment that looked at a house inner courtyard and studied the dramatic, weird roofs and the legendary tubular chimneys. During a two -week stay, he made his first canvas in Parisian roofs and began to interest the different green chairs in the Jardin du Luxemburg a few months later, during his walks with my mother from an apartment in Port Royal.

With a few two-week two-week visits in the past four years, Johnson has continued to deal with the different Paris area. In my view, the ephemeral of these visits has retained his interest in the city, while the frequency of its occurrence enables him to constantly withdraw the layers – to constantly deepen his understanding of this space.

In “Paris (a window)” (above) (above) a work of 2025 at Galerie Mercier can be seen, there is a sensitivity and understanding of Paris – the result of years you're looking for. Just as decades of visits to Truro influence the secret of “Corn Hill”, the repetition of the regular Paris Paris also shapes this new work. “Paris (a window)” distilling the roof in triangles and trapezoids. Johnson examines how shadows interact with the dramatic tendency of the structure, since the Paris roof – like the New England Beach Stuhl – becomes a medium and not on the subject.

Pissarro and Johnson both assumed the challenge of researching uniquely Paris motifs and urban landscapes without getting involved in iconography or report. Pissarro was convinced of how the clearly new Hausmann structures and iconic parks turned with light and the time of day – an approach that was repeated by my father, fascinated by the changing shadows that were cast over zinc roofs and under the green metal chairs of the Jardin du Luxemburg. Both artists were based on their technology in dialogue with the qualities that define Paris, and created works that cause the essence of the city and at the same time distinguishes what its own visions are. Their time on the landscape enabled them to find themselves as a painter before they entered the iconic and complex Paris region and ensured that they have never lost their self -confidence or astonishment in the middle of the boulevards.

Having the opportunity to experience “Paris (a window)” recently – in addition to Johnson's works from California, New England and New York – it is proof of its ability to keep this duality: to capture the spirit of a place and at the same time keep focus on the central elements of color, light and shape.

See more online from Mitchell Johnson's art online.